Let’s start by making something perfectly clear: I love Star Wars. I live and breathe Star Wars. They’re some of my favorite movies, games, and comics; I’ve read more than my fair share of Star Wars fanfiction and have, over the years, spent a ludicrous amount of money on merchandise and other paraphernalia.

When someone, tasked with buying me a gift, asks for ideas, I give them one instruction: if it has Star Wars on it, I’ll like it.

But even if you’re not as Star Wars obsessed as me (it’s hard, I know) — even if you’ve never seen the films — it’s inescapable, as one of the most popular and beloved film franchises of all time. Even Star Wars Luddites possess an awareness of the major characters, concepts, and plots; Star Wars is a cornerstone of our modern, media-obsessed culture. Yet despite this popularity and its trailblazing approaches to special effects and filming, the Star Wars franchise offers a mixed bag when it comes to the representation of female characters’ visibility and autonomy.

Padmé Amidala and the Mystery of the Wasted Potential

Through the six films, women appear in the background and sometimes have a few lines, but even the major female characters (or character – there’s usually only one major woman per film) have little to do compared to her male counterparts. In Episodes I and II, Padmé (Natalie Portman) was a powerful political figure and her position was integral to the larger plot. In The Phantom Menace, as Queen Amidala, her and her girl gang of lookalikes (one of which is a young Keira Knightley) fend off the invading Trade Federation and reclaim their planet, Naboo.

She refuses to be sidelined in the conflict or to remain in safety on Coruscant (against Palpatine’s advice), choosing to independently fight for the freedom of her people. Padmé reaches out to the Gungans, the native people of Naboo, for aid in the Battle of Naboo, uniting them with her people in throwing off their oppressors. Yet she is also conscious of the oppressive colonial history of her people against the Gungans; she proceeds in Attack of the Clones to share her place in the Galactic Senate with a Gungan representative and return to the Gungans their rightful power in Naboo’s political affairs and future.

Oh, and her outfits are gorgeous. I promised myself not to harp on about how beautiful Natalie Portman is, because that’s not the point and she’s not just the eye-candy of the Prequel Trilogy, but one has to respect all the extravagant outfits she dons through the three movies. I’m not usually one for costuming, but when I tried to pick a favorite dress of Padmé’s I ended with five or ten top contenders that I couldn’t choose between. All of them draw from European and Asian traditions, yet mix in a beautifully cohesive Star Wars fashion. It’s amazing, and they definitely suit both Natalie Portman and the character.

But above all else, Padmé is devoted to public service and democracy, and stands up for these ideals when Palpatine dissolved the Republic to create the Galactic Empire.

Okay, maybe it wasn’t so smart to appoint Jar Jar Binks as a representative in the Republic considering he motioned to appoint Palpatine with emergency powers to combat the Separatist threat (although Palpatine was manipulating almost everyone in the Republic at the time — hence the “thunderous applause”). Maybe her outfits are a bit absurd sometimes. And maybe she should have been a little more concerned when Anakin said that dictatorships and totalitarianism are totally OK. Lay off. She’s allowed to make some mistakes.

Love can’t save you, Padmé . Only my new powers can.

ANAKIN SKYWALKER, LADY-KILLER (LITERALLY), AS HE STRANGLES A PREGNANT WOMAN

Yet in the Prequel Trilogy’s conclusion, Revenge of the Sith, her political plotline mysteriously disappears. Deleted scenes from the film show Padmé in meetings with the Delegation of 2000 who, fearing a crumbling democracy, form the beginning of a peaceful rebellion. While remnants of the plotline remain within the film, those that feature Padmé in an active role fell to the cutting room floor – and with them, the ratio of her scenes to those of comparable male characters fell too. She instead becomes a spectator to political debates rather than an active participant, making it not only an issue of visibility (that is, the amount of time she is shown) but also of autonomy.

Most egregious in showcasing her lack of autonomy in Revenge of the Sith is her death. After Anakin falls to the dark side, Padmé dies because she has “lost the will to live.” The meaning (and issue) here are clear: without a male character and love interest, Padmé has no purpose in the plot, and so she dies. The viewer knew all through the Prequel Trilogy that Padmé probably wouldn’t make it (or that she would suffer some awful fate) given what Leia said in Episode VI and that Luke and Leia were raised as orphans. But her death as Lucas wrote it demotes her to an accessory of the male rather than her own person, and seemingly happens only to propel the male character’s plotline (when he learns of Padmé’s death, Anakin loses any remaining shreds of his humanity and becomes Darth Vader). Padmé stands among many other female characters in science-fiction and fantasy films with undeveloped potential and who reinforce the idea that women exist only to serve and to support male-centric plots.

Our Daughters’ Daughters Will Adore Us

Conflicting with Padmé’s diminished role, Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher), the principal female character of the Original Trilogy, enjoys much more agency. She, like Padmé, is an important political figure and a central leader in the Rebel Alliance. A New Hope opens, after all, with the Empire’s “sinister agents” taking control of her starship. In all her audacious and valiant glory, Princess Leia stands up to motherfucking Darth Vader and pretends that she’s just a senator on a diplomatic mission to Alderaan, that she totally didn’t just fly through a restricted star system, and definitely isn’t a member of the Rebel Alliance.

Through the Original Trilogy, Leia often directs and commands both her male counterparts (Han and Luke) as well as the Rebel army. A New Hope, has all the trappings of a classic damsel-in-distress story: with Princess Leia captured by Darth Vader, it’s up to the male characters to rescue her. Yet when they free her from her holding cell, Leia immediately seizes control of the rescue attempt, berating Han and Luke for their incompetence and lack of a plan.

Characters notice and are annoyed by Leia’s domineering personality, but she’s never shamed for it. Han comes close to telling her to shut up in Empire Strikes Back, but only so he can fly them out of the asteroid monster’s mouth that they accidentally landed in (“No time to discuss this with a committee” / “I am not a committee!”), but he admires her spirit and sees her not as a princess but as a person (a relationship that others explore in more depth). The characters and the audience grow to love and admire Leia for challenging male control and exercising her agency.

The metal bikini Leia sports in Return of the Jedi is one of the franchise’s most famous (or infamous, depending on who you ask) images. She dons it when she’s captured by the gangster Jabba the Hut and becomes his personal slave; the movies never show the parameters of this enslavement, but given the outfit, it’s no stretch to say there is a sexual element to it. ‘Slave Leia’ and Carrie Fisher became something of a sex symbol in the wake of the film. Some ‘Slave Leia’ fanboys may claim the infatuation merely lies with the revealing nature of the outfit and Carrie Fisher’s svelte body, but there are undeniable fantasies of control and domination mixed in (she literally has a chain around her neck). But Star Wars fans have made recent efforts to rebrand ‘Slave Leia’ as ‘Leia the Hutt Slayer’ (a nod to Buffy the Vampire Slayer), as, in the film, she overpowers and murders her captor. The plot point then transforms into an empowered woman fighting against objectification and forced sexual submission, and reclaiming her lost autonomy.

This Isn’t the Film Franchise You’re Looking for, Sexists.

This is by no means an exhaustive study of women in the Star Wars universe, or even Padmé and Leia, but even this cursory look reveals the series’s burdened relationship with women. Of course, despite the many failings of the franchise to represent women, I am an enormous fan of the series, and I feel it’s not all bad. Growing up, Leia unquestionably influenced me; I loved this powerful, brazen woman who was also allowed to be tender and human, who matched and occasionally superseded her male counterparts. While I take issue with how Padmé is portrayed in Revenge of the Sith, before that she is at least allowed to be clever and political. Mostly, it’s upsetting for me that that potential was wasted.

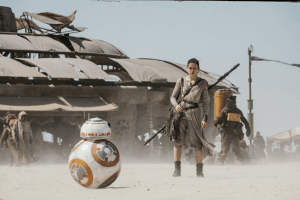

Perhaps I’m more prone to give Star Wars a pass because I love it, but I feel there are some positive representations of women to be found in the six movies. Happily, Disney seems resolved to remedy that with The Force Awakens. The film is still under wraps at the time of writing, and I’ve placed myself in a Force Awakens silo after the second theatrical trailer, but Rey (Daisy Ridley) has been featured prominently in promotional materials and merchandise — and she won’t be shafted like Padmé or Leia if Carrie Fisher has anything to do about it:

Fisher: Oh, you’re going to have people have fantasies about you! That will make you uncomfortable, I’m guessing.

Ridley: Yeah, a bit.

Fisher: Have you been asked that?

Ridley: No, they always talk about how you’re a sex symbol, and how do I feel about that. [Fisher sighs] I’m not a sex symbol! [laughs]

Fisher: Listen! I am not a sex symbol, so that’s an opinion of someone. I don’t share that.

Ridley: I don’t think that’s the right—

Fisher: Word for it? Well, you should fight for your outfit. Don’t be a slave like I was.

Ridley: All right, I’ll fight.

Fisher: You keep fighting against that slave outfit.

Ridley: I will.

The pervasiveness and popularity of Star Wars poises it to be another dissenting voice against sidelining women in favor of male heroes. There are tons of female fans of the franchise, and portraying women more consistently and positively can only convert a new generation of girls to Star Wars fandom, as well as prove that action movies don’t need rugged, domineering male heroes to succeed; they can, in fact, actively and explicitly subvert sexist notions. I’m looking forward to The Force Awakens for a lot of reasons, but seeing where Rey falls in the lineage of Star Wars ladies before her falls near the top of my priorities. There’s a solid legacy before her, but one with plenty of room to improve.

I originally wrote this for an assignment in a Women’s Studies course; I have modified the tone and expanded the content for this blog.

Leave a Reply