Set in the fictional town of Arcadia Bay, Life is Strange follows Max, the recently minted 18-year-old photography nerd, attending the elite Blackwall Academy. In the trend of episodic games, Life is Strange centers around player choice, the butterfly effect being both a literal and figurative force in the game. It manages, however, to distinguish itself from not only Telltale Games — with its unique center and focus on two teenage girls, as well as its gorgeous, indie-film presentation — but also from just about everything else we’re seeing in gaming today.

Max shares the profile that I’m sure many gamers, myself included, occupied in our high school days — the slightly dorky, quiet kid in the back, who drifts through the hallways with earbuds in, avoiding the ritualistic and cult-like social hierarchy. Life is Strange manages to toe a line, careful that Max does not come off too snobbish or superior (a territory I am also familiar with) — in her journal and commentary, she expresses a conflict between wanting nothing to do with her fellow students, particularly those belonging to the “Vortex Club,” and acknowledging that many of them are kind or interesting and that there are rewards for giving them a chance. It’s a thoughtful portrayal of teenage and high school tropes, and one of the only high school-set stories to remind me of my own experiences rather than other media’s shallow and flat idea of what high school is. Fairly early into the episode, however, Max realizes an alienating factor in herself that I’d wager players may not find as relatable — the ability to control and rewind time.

It’s a thoughtful portrayal of teenage and high school tropes, and one of the only high school-set stories to remind me of my own experiences rather than other media’s shallow and flat idea of what high school is.

The mechanic is a refreshing twist on the choice-based episodic game trend, and one that functions especially well in the setting. How often in our high school careers do we wish we could relive something — would we have answered the teacher’s question differently? Been more delicate to a friend? Wore a pair of pants that wouldn’t rip down the rear? And yet, Max’s new-found power is far from a blessing; the player must predict the long-term consequences of a choice that satisfies them immediately, often selecting the option with less desirable instant results in pursuit of future pay-off. Like Pavlov’s bell, the “this action will have consequences” icon and accompanying sound began to trigger an actual feeling of hesitation and anxiety in me, an effect that speaks to how engrossing the game is.

I tried to resist the urge to rewind everything, and to instead trust my instincts, though I struggled along the way. After every decision made, Max will second-guess her (and therefore, my) choice, wondering if she should rewind. Even though we can see the immediate consequences of a decision play out, it doesn’t make the decisions any easier to make than in a game like Mass Effect; if anything, they’re more difficult in Life is Strange, because we always have the option to renege.

Many of the choices Life is Strange presents regard privacy, a motif that helps authenticate it as a realistic portrayal of the teenage experience. In most video games, an NPC will stand by happily as you raid their belongings. In Life is Strange, there are consequences for rifling through someone’s possessions — you’ll discover information you’d rather not have known, or trespass on someone’s trust and hospitality. Other times, you’re able to lend a sympathetic ear to, say, a girl with a secret pregnancy. Here the time travel mechanic works in the player’s benefit; if a character objects to you learning their secrets, you can merely go backwards with the information still in mind but without the negative ramifications.

Whatever the specific situation it appears in, the choice-based gameplay of Life is Strange feels incredibly natural in the setting, as adolescence is traditionally a period of establishing one’s identity. What may ordinarily be mundane decisions, therefore, have an added weight. From the very start of the game, reading Max’s journal entries, we’re confronted with the harrowing and persistent question that possesses every teenager, and that we must grapple with it every time we’re prompted for a choice: What type of person do I want to be?

The title of Chrysalis is, therefore, well-applied by Dontnod, not simply as a metaphor for the transitional period between adolescence and adulthood. It’s also a quiescent stage, a dormant phase, a chapter that enables introspection — which Life is Strange also portrays, in Max’s internal dialogue, and through the recurring symbols of mirrors and selfies. The player is able to look at Max from both the interior, by controlling her, and the exterior. And like when taking a selfie, we’re allowed to select how to portray ourselves — what light we’d like to place ourselves in, what expression to make, what message the picture creates and communicates.

Having only just left my teenage years, I feel right at home in Life is Strange. I understand Max. I relate to her. I see myself in her, and her in me. And that’s an incredibly rare experience for a female, teenage gamer.

On the topic of Life is Strange placing selfies in a positive light, I have to praise the game for celebrating teenagers — both their good and bad — and teenage girls at that. Having only just left my teenage years, I feel right at home in Life is Strange. I understand Max. I relate to her. I see myself in her, and her in me. And that’s an incredibly rare experience for a female, teenage gamer. Now of course, Dontnod’s use of teen culture can be somewhat heavy-handed; some of the slang is inserted clumsily into the dialogue (“You hella saved my life”), some of Blackwall’s students are rather trope-y (at least, right now — they may be developed in future episodes, and tropes are valid building blocks), and the overall atmosphere of Blackwall is just a little too hip to be totally believable. Even Max insists on using a retro, Polaroid camera. These problems did momentarily remove me from the game, but they are minor alongside an otherwise believable and realistic world. At a certain point, you’re sucked far enough into the painterly visuals, exaggerated sunsets, ambient soundtrack, or well-placed indie track (personal favorite song and perhaps scene? The birds-eye view of Chloe smoking to Angus & Julia Stone) that you don’t feel these bumps in the road. It pokes fun at the selfie (a character at one point tells Max to “go fuck your selfie”) and my generation’s addiction to social media, but it never extends to mocking or disdain; rather, these are important aspects of today’s teenage experience and they deserve to not only be portrayed, but to be celebrated. Life is Strange turns the stigma of teenage girls around 180 degrees — Max isn’t an enjoyable character because she’s “not like other girls” or any similarly misogynistic statement. She is like most girls. And she’s great. One character in particular could have flopped and ruined the entire experience of Life is Strange, fallen into the manic pixie dream girl trope that lines modern-media — and gratefully, that’s not the case.

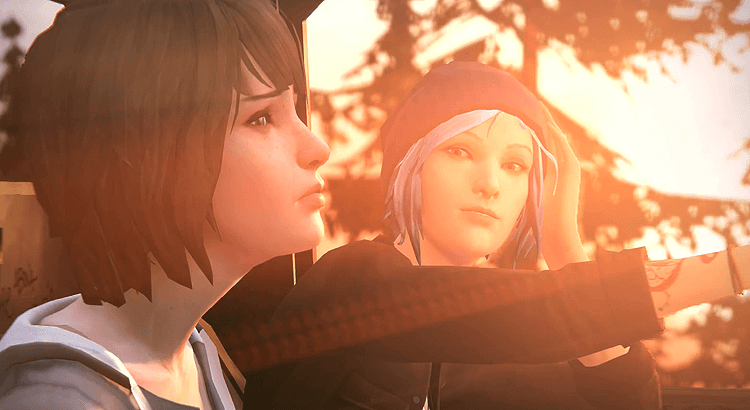

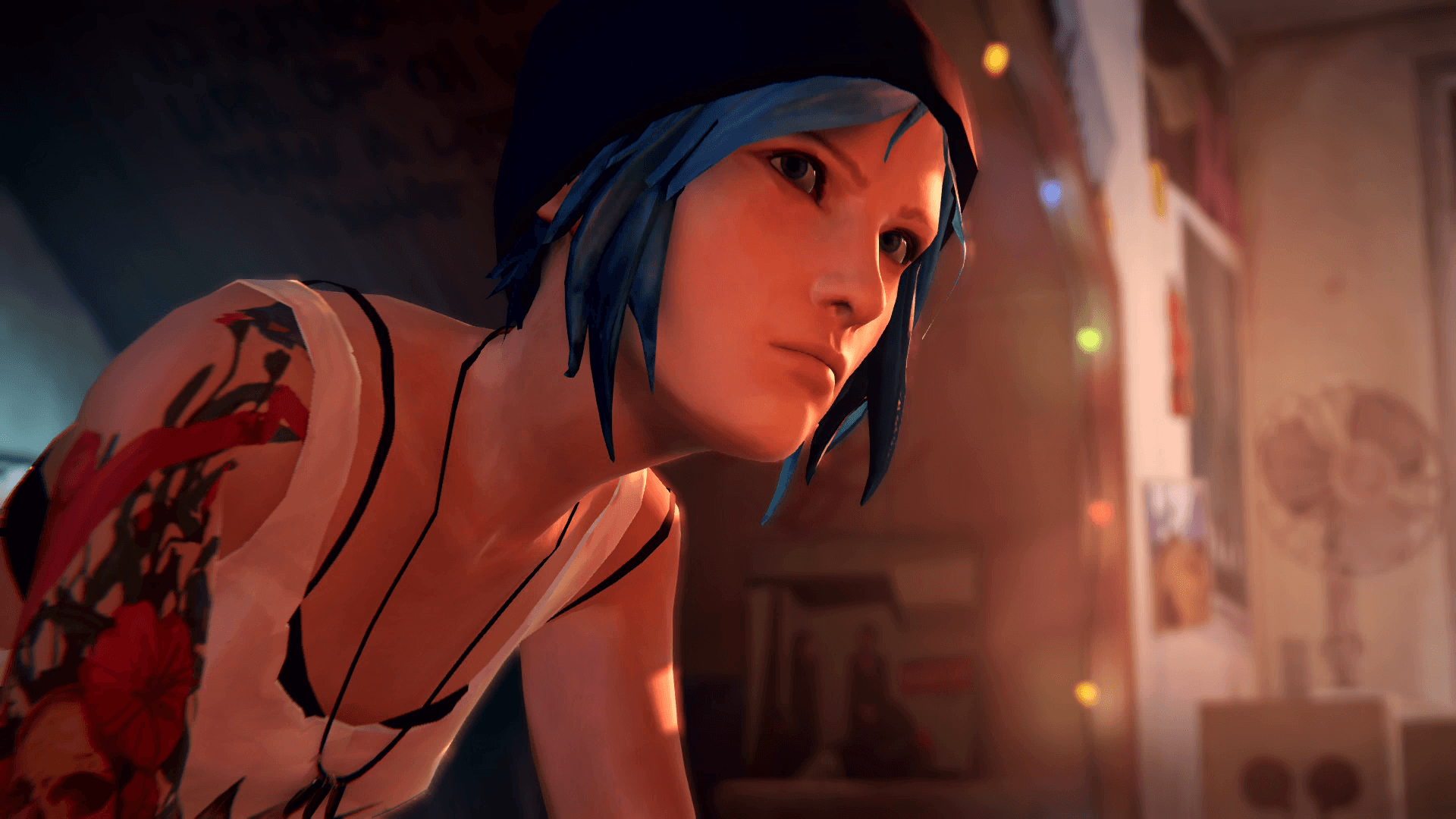

If Max represents the incubation period implied by the episode’s title, Chloe is the hard outer shell. Despite being heavily advertised, Chloe doesn’t make a formal appearance until at least halfway through the episode — but her introduction is all the more exciting for it. She has this sort of looming, mysterious presence before we actually see her, let alone are introduced to her as Chloe — through Max’s journal, we learn the girls’ backstory: they were inseparable until Max moved to Seattle and, for whatever reason, never contacted Chloe again. When the two eventually reunite, Chloe isn’t at all what Max expected.

I won’t beat around the bush. I love Chloe. I spent less than two hours with Chloe and I think she has the potential to be one of this gen’s most memorable characters. She could easily have become a pothole on the manic pixie dream girl (despite noted issues with the term), wish-fulfillment road, and to be fair, there is a degree of this going on. But as TV Tropes notes:

Despite all that (or because of all that), there are ways of utilizing this trope without falling into that pitfall. Given enough time, Character Development can add to their personality and interests and pull them away from the MPDG foundation. The story may even be told from their perspective, revealing that there is more to them than bringing adventure to brooding guys. Deconstructions of the idea may show that they resent being considered only useful for the benefit of the main character, idolized as something that they are not, or that once the main character reaches their “enlightened” stage, the MPDG moves on to the next person who needs their help.

In just the first episode, Chloe has already been fleshed out better than anything other character (rightfully so, as she’s the deuteragonist) besides Max, with enough mystery to carry us through more development and character arcs. She boasts a mix of abandonment and daddy issues, is an assault survivor, and has a seriously dysfunctional home situation. Again, Dontnod treads some dangerous ground here, but has yet to use step in any cringe-worthy manner (that I picked up on, at least). It’s refreshing to see these issues portrayed in a character without them overwhelming or otherwise defining the character. Chloe isn’t interesting because she’s had a rough life; she’s more relatable and realistic for it, but these traits aren’t thrown in carelessly. She’s a character with an immense energy, depth, and charisma. She’s tough and she’s complicated and she refuses to take shit from anyone, even Max. I’ve scarcely seen this level of nuance in female characters, let alone supporting female characters, in video games.

She’s a character with an immense energy, depth, and charisma. She’s tough and she’s complicated and she refuses to take shit from anyone, even Max. I’ve scarcely seen this level of nuance in female characters, let alone supporting female characters, in video games.

Oh, and she’s probably queer, based off of some of her decorative choices and her affectionate descriptions of Rachel. I’m aware that I have perhaps cultivated a reputation for assuming most female characters are queer, even without pre-existing subtext — I don’t deny that. But as infatuated as I am with Chloe, as both a character and for what she represents, I don’t think I’m reaching here. That said, at its heart — without the science-fiction and supernatural elements — Life is Strange is a story of female friendship, how two young women reunite and support one another as they face adulthood. Despite both being rather pragmatic, they acknowledge that something — destiny, perhaps? the butterfly? — brought them together for a reason. It’s no coincidence that Max’s powers appear just in time to save Chloe’s life. Whether romance becomes part of that remains to be seen; even with my inclination to pair off female characters, Max and Chloe’s interactions have been fairly platonic thus far. I’d be delighted to see that change, but equally pleased if Dontnod makes a conscious design to not change it — to instead craft a (female) bildungsroman that doesn’t culminate in romance, and to celebrate female friendship and sisterhood without sexualizing it or its characters.

Life is Strange‘s first episode managed to deliver on, and exceed, every one of my expectations for it. The first chapter concludes with a slideshow of the vivid characters encountered, who will no doubt hold further significance to the story as Arcadia Bay’s many mysteries unfold, all under the foreboding threat of a coming storm — the tornado Max dreams will hit the town in just four days. As the episode faded out, I watched the credits roll by, the incredible mood and atmosphere still encircling me, and it lingered for days after. There is still so much for me to explore in-game and to talk about outside of it; if nothing else, that’s the mark of a fantastic release — one that inspires me to talk about it, to analyze it; one that draws me into it and back to it several times. Life is Strange is not a game that anyone would bank on as a success in an industry so inundated with guns held by rugged white guys; it set out with a vision to create a modern-day, women-driven Twin Peaks, and succeeded. It’s a refreshing change from an industry that is otherwise rather trapped in sameness and stagnation. I have a big journey left to take with Max and Chloe and, judging by its first steps, it will be quite a ride.

Leave a Reply